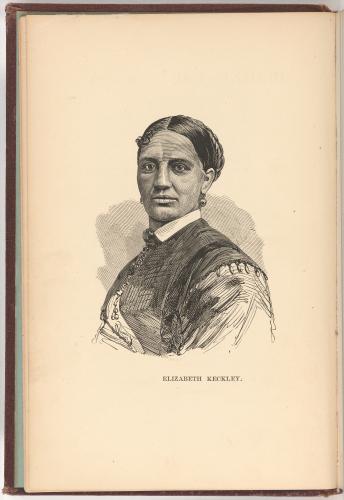

Portrait of Elizabeth Keckly appearing as the frontispiece of her book, Behind the Scenes or Thirty Years A Slave, and Four Years in the White House, published in 1868. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Elizabeth Hobbs Keckly (often spelled “Keckley”) was an African American seamstress and author. While often remembered for her association with First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln, Keckly was also notable as a resolute woman who purchased her own freedom, provided relief to freed slaves during and after the Civil War, and wrote an autobiography detailing her extraordinary life.

Born in 1818, Keckly was the only child of her mother Agnes, a literate, enslaved domestic servant, and her enslaver, Virginia planter Armistead Burwell. Agnes was an expert seamstress and passed on her literacy and sewing skills to her daughter. Keckly began working in her father’s household as a young child, and at the age of fourteen she was sent to work for Burwell’s oldest son and his wife. While there, hardship and physical abuse defined her teenage years. By the time she was a young adult, she was being repeatedly raped by a member of the community, which eventually resulted in the birth of her only child, George.

Christening gown of Alberta Elizabeth Lewis-Savoy made by Elizabeth Keckly in 1866. Division of Home and Community Life, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

Soon after the birth of her son, Keckly began serving the family of Burwell’s daughter Ann Garland. In 1847, the Garlands moved to St. Louis seeking business opportunities and took Agnes, Keckly, and George with them. The family struggled financially in St. Louis and began to hire out Keckly as a seamstress to generate income. From this, Keckly adeptly built a business and clientele among the socially prominent women of the city.

Prior to her marriage to James Keckly in 1850, Elizabeth negotiated the purchase of her own freedom and that of her son, George. After many attempts to earn or raise the $1200 purchase price, a loyal patron raised the needed sum, and Keckly became a free woman in 1855. Though the money was intended as a gift, Keckly would only accept it as a loan and spent several more years working to repay the debt. She ended her marriage after eight years, only noting that James Keckly was “a burden instead of a helpmate.”1

Mary Todd Lincoln’s velvet day dress made by Elizabeth Keckly in 1864. Division of Political and Military History, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

In 1860, Keckly moved to Washington, D.C. and began building a dressmaking business that once again catered to wealthy and influential women. In 1861, a client recommended her to the President’s wife, Mary Todd Lincoln. Keckly soon became the First Lady’s personal dressmaker and developed a close friendship with her and the family in the White House. Keckly’s business prospered, allowing her to employ 20 women in her dressmaking shop. With other women in her church, she formed a relief association to assist the many formerly enslaved people in the city.

Photograph of Mary Todd Lincoln by Matthew Brady Studio, around 1863. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

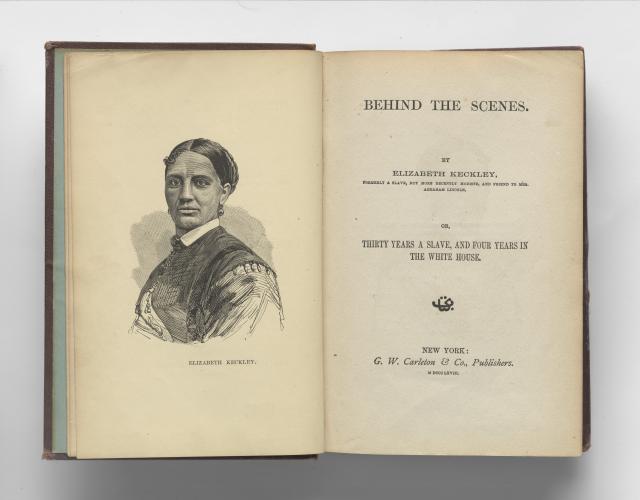

Mrs. Lincoln relied upon Keckly’s companionship and assistance in the weeks after her husband’s assassination, and after her return to Illinois they corresponded frequently. Experiencing financial difficulties, Mrs. Lincoln determined to raise money by selling her White House wardrobe and asked Keckly to meet her in New York City to assist in the transaction. It was a poorly conceived endeavor on Mrs. Lincoln’s part that resulted in public scandal and criticism in the press. In 1868 when Keckly detailed the event in her autobiography Behind the Scenes or Thirty Years A Slave, and Four Years in the White House, she sought to defend the former First Lady. However, her white readers were dismayed to find the details of private conversations and meetings related in the book. It violated norms of privacy, race, and social class for a free Black woman to write a memoir detailing the personal concerns of the former President and First Lady. The press openly criticized Keckly, while Mrs. Lincoln felt personally betrayed and ended their friendship. Keckly’s business suffered as a result. Unlike earlier books written by formerly enslaved persons, sales of Keckley’s autobiography were weak, and there was little interest in her as a speaker. Additionally, Mrs. Lincoln’s son, Robert, may have suppressed the distribution of the book.

Frontispiece and Cover Page from Behind the Scenes or Thirty Years A Slave, and Four Years in the White House by Elizabeth Keckly, 1868. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

After the publication of her autobiography, Keckly persevered as a dressmaker, and she became known for training young African American seamstresses. In 1892, she accepted the position as the head of the Department of Sewing and Domestic Science Arts at Ohio’s Wilberforce University. After suffering from a stroke in the late 1890s, she returned to Washington D.C. and spent her final years in the National Home for Destitute Colored Women and Children, an institution descending from the relief association she founded at the beginning of the Civil War. Keckly died in 1907.

Endnotes:

1 Keckly, Elizabeth, Behind the Scenes, or Thirty Years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House (Original publication: G.W. Carleton & Co, Publishers, 1868. Reprint: Eno Publishers, 2016): 21.

Further Reading:

- Elizabeth Hobbs Keckly, Behind the Scenes or Thirty Years A Slave, and Four Years in the White House, 1868.

- Carolyn Sorisio, “Unmasking the Genteel Performer: Elizabeth Keckley’s Behind the Scenes and the Politics of Public Wrath,” African American Review 34 no. 1 (Spring, 2000): 19-38.

- Jennifer Fleischner, Mrs. Lincoln and Mrs. Keckly: The Remarkable Story of the Friendship Between a First Lady and a Former Slave, 2003.

- Lina Mann, “From Slavery to the White House: The Extraordinary Life of Elizabeth Keckly,” White House Historical Association, https://www.whitehousehistory.org/from-slavery-to-the-white-house-the-extraordinary-life-of-elizabeth-keckly.

Related Posts

Diana Turnbow provides research and project support to the Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum.