Geneva Townes Turner. Anacostia Community Museum, Smithsonian Institution.

By Diana Turnbow, administrative assistant for the Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative

Volunteers with the Smithsonian Transcription Center turn handwritten and typed documents into machine-readable resources. Made available on the web, stories in transcribed documents are preserved and made permanently searchable as the original documents age. Thus, the content from transcribed resources is more easily available for everyone.

The Smithsonian’s collections include more than 155 million objects, including millions of pages of text and data. Thanks to thousands of volunteers at the Smithsonian’s Transcription Center, many more of our documents now have readable text. As of this spring, these volunteers have transcribed more than one million pages of original material!

Transcription often shines a spotlight on lesser-known stories of women, people of color, and other marginalized groups. In honor of one million pages transcribed, here are four African American women whose stories have been amplified through transcription:

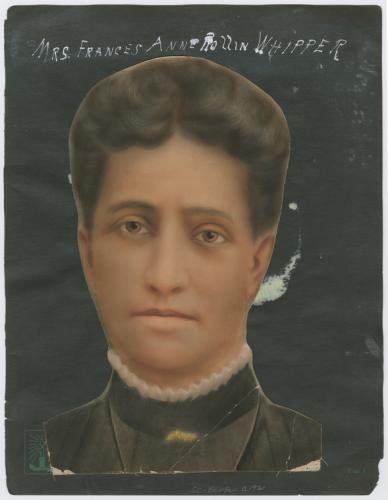

1. Author Frances Anne Rollin

Portrait of Mrs. Frances Anne Rollin Whipper, 1870-1879. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library.

Frances Anne Rollin was born into a prosperous family in the small, influential community of free people of color in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1845. Her father, William Rollin, was a merchant and lumber dealer from an aristocratic family in the former West Indian French colony of Saint Domingue. Her mother was also from the French Caribbean.

Before the Civil War, her father sent Rollin to Philadelphia to attend The Quaker School for Colored Youth. In Philadelphia, Rollin developed as a writer and became an activist in support of women’s suffrage and civil rights.

After the war, Rollin returned to South Carolina and started teaching at a Freedmen’s school. She gained notoriety in 1867 when she filed a claim against the captain of a steamship for denying her access to the first-class cabin while traveling between Charleston and Beaufort, South Carolina. Major Martin R. Delany, the army’s highest ranking Black commissioned officer, assisted Rollin with the court proceedings. The court ruled in favor of Rollin and fined the steamship’s captain $250.

An abolitionist, journalist, and proponent of Black nationalism, Delany commissioned Rollin to write his biography. Rollin moved to Boston and worked for eight months on the manuscript. While in Boston, she had an active social life and interacted with notable abolitionists and public figures. In 1868, she published Life and Services of Martin R. Delany under the name Frank A. Rollin. Like many women writers in the 19th century, Rollin deliberately used her nickname of “Frank” to hide her gender to avoid prejudicing her readers.

After completing the biography, Rollin accepted a clerkship with South Carolina state representative William J. Whipper, a Black attorney originally from Pennsylvania. Whipper was the only state representative to endorse women’s suffrage at South Carolina’s 1868 Constitutional Convention. Rollin and Whipper married and became a power couple in Republican circles in the state’s capital.

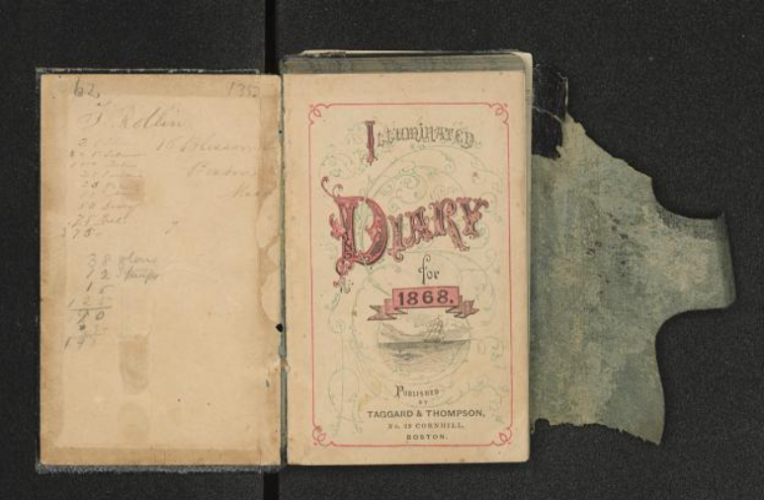

Rollin’s 1868 diary is now in the collection of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. The diary describes her life in Boston, as well as her courtship and early months of marriage to Whipper. This resource is one of the earliest known diaries by a Southern Black woman.

Diary of Frances Anne Rollin, 1868. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of the Carole Ione Lewis Family Collection.

2. Maternal Care Provider Dr. Ionia Rollin Whipper

Dr. Ionia Rollin Whipper. Image courtesy The Ionia R. Whipper Home, Washington D.C.

Frances Anne Rollin’s daughter, Dr. Ionia Rollin Whipper initially trained as a teacher and worked in Washington public schools for 10 years before attending medical school. She graduated from Howard University School of Medicine in 1903, one of four women in her class.

After serving as a resident physician at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, she established a private practice for women in Washington, D.C. Whipper specialized in obstetrics, the medical field focused on pregnancy and childbirth.

From 1921 to 1929, Whipper worked as an assistant medical officer for the Children's Bureau of the U.S. Department of Labor. She traveled throughout the rural South training midwives and advocating for improved public health policies and practices.

When she returned to Washington, Whipper began working in the maternity ward of Freedmen's Hospital. There she began to mentor many teenage mothers who lacked family or support networks. With the help of a small group of women from her church community, African Methodist Episcopal St. Luke's, Whipper raised money to open a home for unwed pregnant girls in 1931. The Ionia R. Whipper Home for Unwed Mothers was the only maternity home for young African American women until the 1960s. It remains open to this day, serving at-risk girls and women from ages 12 to 21.

Like her mother, Whipper kept a journal, which provides insight into her spiritual and intellectual life. Whipper’s journal from 1939 is part of the collection of the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

3. Community Health Advocate Dr. Matilda Evans

Dr. Matilda A. Evans, around 1930. Photograph by Richard S. Roberts. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Leatrice Trottie Brown in memory of Dr. Matilda A. Evans.

Dr. Matilda Evans was the first African American woman licensed as a physician in South Carolina. With help from a benefactor, Evans attended the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania. Her examination certificates from 1896 in the National Museum of African American History and Culture’s collection, list her areas of study. Her practice in Columbia, South Carolina focused on obstetrics, gynecology, and surgery. Her skill and professionalism allowed her to build a large interracial practice. The income from wealthy patients enabled her to treat women and children with lower incomes without charging them.

Before the civil rights legislative reforms of the 1960s, many hospitals refused to admit African American patients, or employ African American healthcare professionals. Evans cared for Black patients in her own home until she established the Taylor Lane Hospital in 1901. It was the first African American hospital in Columbia. After a fire destroyed the hospital in 1911, Evans established the St. Luke’s Hospital and Training School for Nurses. Her own farm supplied dairy and produce to these hospitals.

Evans supported her African American community by promoting health education. She created the Negro Health Association of South Carolina, and published a weekly newspaper centered around nutrition, hygiene, and recreation. Evans also built and operated a community swimming pool and recreation center on her own property. It was the only facility available to African Americans in Columbia.

She provided vaccinations and other preventative care for families through free clinics. Volunteers recently transcribed a newspaper clipping from 1931 about the establishment of the Evans Clinic Association of Columbia, South Carolina.

4. Educator and Researcher Geneva Townes Turner

Geneva Townes Turner. Anacostia Community Museum, Smithsonian Institution.

Geneva Townes Turner was an elementary school teacher in Washington, D.C. In 1919, she married Dr. Lorenzo Dow Turner, the first professionally trained African American linguist . She assisted him with his research on the Gullah language of the Sea Islands off the coast of South Carolina and Georgia. Volunteers transcribed his appointment book from 1932. It reflects the many people he interviewed to learn about Gullah speaking patterns.

As research associate and scribe of her husband, Townes Turner helped with the recordings of Gullah songs and dialect. She studied phonetics to be able to transcribe the Gullah recordings. Turner gained fame as the first linguist to document and identify the Gullah language as a form of Creole. However, Townes Turner was not recognized for her contributions. Wives of famous scientists also often assisted with research without credit. Historian Margaret Rossiter said these women acted as “silent and invisible co-workers" in the historic record.

The pair separated in 1938. Townes Turner returned to teaching elementary school in Washington. She went on to co-author and publish two children’s books: Word Pictures of the Great in 1941 and Pioneers of Long Ago in 1951. Her personal papers are located in the Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum archives.

Related Posts

Diana Turnbow provides administrative support and works on special projects for the American Women’s History Initiative. She is invested in finding and sharing the stories of American women artists and makers.