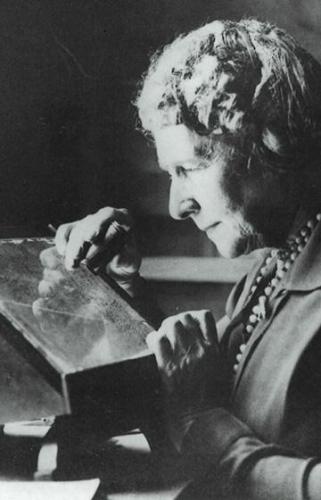

Annie Jump Cannon, Harvard Observatory, Glass Plate Collection.

In the late 19th century, a talented group of women at Harvard Observatory (now the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory) began studying glass plate photographs of the night sky, cataloguing stars and measuring distances across space—an unusual occupation for women of the era. Several of these so-called women computers, employed at Harvard from the 1880s through the 1950s, made groundbreaking discoveries in astronomy and astrophysics but, until recently, received little public recognition for their work.

Harvard and the Smithsonian are teaming up to change that. A joint digitization project is shining a light on these pioneers of astronomy, transcribing and scanning the women's logbooks and notebooks, as well as the glass plate photographs that formed the basis of their research. The project will make the books and photos available to a global online audience for the first time.

Digital volunteers recruited through the Smithsonian Transcription Center are transcribing a trove of 2,400 notebooks and diaries kept by women such as Annie Jump Cannon, who devised a system for classifying stars that astronomers still use today, and Henrietta Swan Leavitt, who discovered a new method of measuring distances between stars, enabling astronomers to gauge the size of the universe.

At the same time, staff at the observatory are scanning more than 450,000 glass plate photographs of stars, taken by Harvard telescopes from 1885 to 1992. By December 2017, the team had scanned more than 200,000 plates.

The project builds on growing public interest in women's historical contributions to science, as portrayed in movies like "Hidden Figures." Harvard's women astronomers are the subject of a 2016 book by journalist Dava Sobel, "The Glass Universe: How the Ladies of the Harvard Observatory Took the Measure of the Stars," which brings long overdue recognition to this remarkable group.