Isabella Aiukli Cornell, a Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma citizen, 2019. Courtesy of Doug Hoke. Part of the Girlhood: It's Complicated exhibition at the National Museum of American History.

By Anya Montiel of the National Museum of the American Indian and the Smithsonian American Art Museum and Sara Cohen of Because of Her Story

This month marks National Native American Heritage Month. Many of our Smithsonian museums document and share Native American history. Here are nine photos, videos, and other objects from our collections about 12 women to know.

1. Theresa Secord

Basket with cover by Theresa Secord (Penobscot). National Museum of the American Indian.

Theresa Secord (Penobscot) has tirelessly taught the art of ash and sweetgrass basketry. As a founding member of the Maine Indian Basketmakers Alliance, she helped inspire more people to become weavers from the Maliseet, Mi'kmaq, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot nations. Through her work, the number of basketmakers grew from 55 to more than 200. Secord became the first U.S. citizen to receive the Prize for Creativity in Rural Life from the Women's World Summit Foundation in 2003. She also received a National Endowment for the Arts National Heritage Fellowship in 2016. You can watch her speak about her research and art at our National Museum of the American Indian in 2015.

2. Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte

Portrait of Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte (Omaha). National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

Susan La Flesche Picotte (Omaha) broke barriers as a woman doctor in the 19th century. She was born and raised on Nebraska's Omaha reservation. At age 14, she left home to continue her schooling, attending the Elizabeth Institute in New Jersey and later the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia (now Hampton University). She continued her education at the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania. She graduated a year early and first in her class. At age 24, she returned home and became the only doctor for more than 1,200 people across more than 400 miles. She made house calls on horseback and later by buggy. After she married Henry Picotte and had two sons, she sometimes brought her children with her on house calls. Towards the end of her life, she solicited enough donations to open a hospital on the reservation in Walthill, Nebraska.

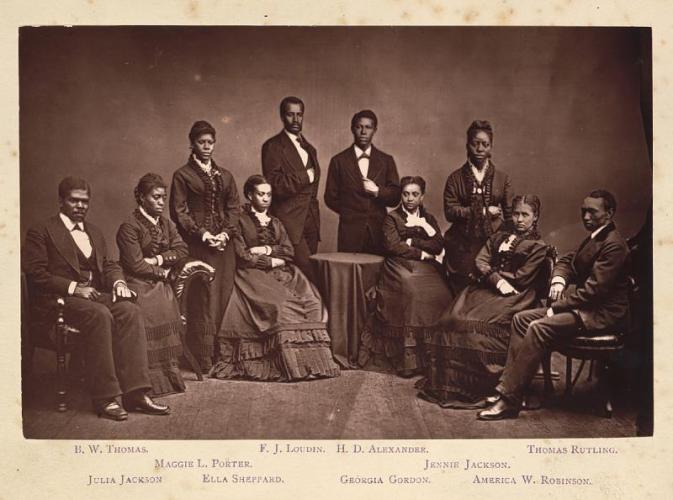

3. Jennifer Kreisberg, Layla Locklear, Charly Lowry, Soni Moreno, and Pura Fé

Founded in 1987, Ulali is an Indigenous women's a cappella group. Ulali is known for their harmonies and a wide vocal and musical range. Current members include Jennifer Kreisberg (Tuscarora), Layla Locklear (Tuscarora), Charly Lowry (Tuscarora), and Pura Fé (Tuscarora). Soni Moreno (Mayan/Apache/Yaqui) is a former member. As Ulali, these women have performed throughout the world, including the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta. Their songs have been featured on the Smoke Signals movie soundtrack, in Robbie Robertson's Music for the Native Americans album, and in the Turner documentary series The Native Americans. Watch Kreisberg, Moreno, and Pura Fé perform "Mother" at the 1997 Smithsonian Folklife Festival.

4. Marie Watt

Marie Watt (Seneca), "Edson's Flag(link is external)," 2004, American flag (from U.S. military burial) with wool blankets, satin, and thread, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Driek and Michael Zirinsky in honor of Jane Beebe and Spencer Beebe, 2015.28.7, © 2004, Marie K. Wat

Based in Portland, Oregon, Marie Watt (Seneca) is a multidisciplinary artist. She is also the first Native American student to receive an MFA from the Yale School of Art. Watt's work draws from Indigenous principles, Native American women's leadership roles, history, and family narratives. Four of Watt's artworks are in the collection of our National Museum of American Indian, including a textile work "In the Garden (Corn, Beans, Squash)" and three works on paper. This textile work, "Edson's Flag," is part of the Renwick Gallery of our Smithsonian American Art Museum. Watt created "Edson's Flag" to honor her great uncle Edson Plummer. Plummer served in the Air Force during World War II. Following his death, his funeral flag was passed down through the family. When it reached Watt, she decided to use it in her work to honor him and other veterans. She has received a Joan Mitchell Foundation Fellowship, Anonymous Was a Woman Award, and a Bonnie Bronson Fellowship Award.

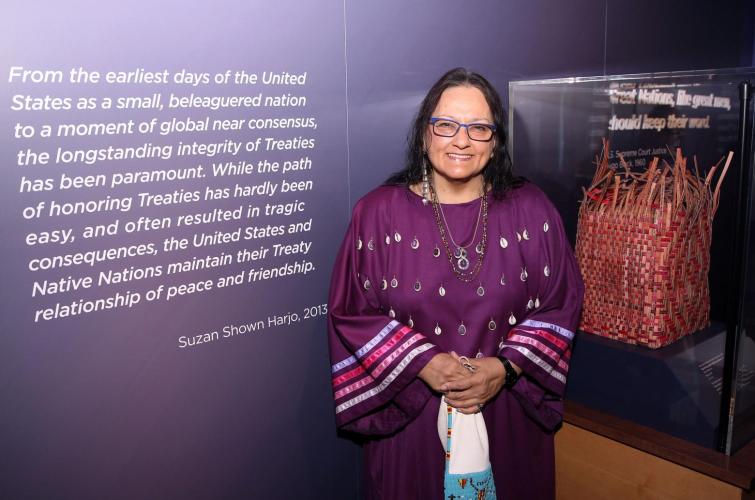

5. Suzan Shown Harjo

Suzan Shown Harjo (Hodulgee Muscogee/Southern Cheyenne) at the National Museum of the American Indian. Paul Morigi/AP Images for The Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian.

In 2014, Suzan Shown Harjo (Hodulgee Muscogee/Southern Cheyenne) received the Presidential Medal of Freedom. As an activist, poet, and journalist, Harjo has fought for Native American sovereignty rights for more than 40 years. These important issues include protecting sacred sites, religious freedom, treaty rights, removing Native American mascots, and language revitalization. Harjo worked as the president of the National Congress of American Indians. She served as a special assistant for Indian legislation in President Carter's administration. Harjo was a founding trustee of the National Museum of the American Indian. She guest curated the museum's exhibition Nation to Nation: Treaties Between the United States and American Indian Nations.

6. Otellie Pasiyava Loloma

Vase by Otellie Pasiyava Loloma (Hopi). National Museum of the American Indian.

Ceramicist Otellie Pasiyava Loloma (Hopi) was born at Second Mesa on the Hopi reservation in northern Arizona. After World War II, she studied at the School for American Craftsmen and later at the Alfred University in New York. She returned to Arizona to operate a pottery shop with her husband, Charles Loloma. She was one of the first faculty members at the Native American arts school, the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico. She taught ceramics and painting for 26 years. Loloma encouraged her students to experiment with techniques, materials, and forms.

Sculpture by Otellie Pasiyava Loloma (Hopi), 1922–1993. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Gift of S.C. Johnson & Son, Inc.

7. Isabella Aiukli Cornell

Isabella Aiukli Cornell, a Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma citizen, 2019. Courtesy of Doug Hoke. Part of the Girlhood: It's Complicated exhibition at the National Museum of American History.

In 2018, Isabella Aiukli Cornell (Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma) used her prom dress to raise awareness about missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. According to the Department of Justice, American Indians and Alaskan Natives are two and a half times more likely to experience violent crimes and at least two times more likely to experience rape or sexual assault crimes in comparison to other ethnicities. Experts believe even more crimes go unreported. In 2019, the U.S. began a federal investigation into missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

Cornell chose a red prom dress because red represents the movement to end this crisis. She has been part of the movement since she was a teenager. Cornell is also a member of Matriarch, an organization that works to create a safe space for Native women experiencing violence. Cornell asked the dress designer, Della BigHair-Stump (Crow), to include a cultural design on the top as well. The diamond pattern represents the diamondback rattlesnake. The Choctaw Nation considers the rattlesnake, who protected the crops, an important relative. Cornell said, "Today and always we remember and honor our missing and murdered Indigenous women. They are not forgotten. Bring them justice. Bring them home."

8. Ofelia Zepeda

Dr. Ofelia Zepeda, the featured author for the October 2008 Vine Deloria, Jr. Native Writers Series at the National Museum of the American Indian in D.C. with poet Terence Winch. Photo by Katherine Fodgen for the National Museum of the American Indian.

Poet and linguist Ofelia Zepeda, PhD, (Tohono O'odham), wrote the first grammar book on the Tohono O'odham language, a language spoken by Indigenous people of the Sonoran Desert area of Arizona and northern Mexico. Zepeda also co-founded the American Indian Language Development Institute. The Institute revitalizes Indigenous languages across generations. Today, she is the director of the institute. In 1999, she received a MacArthur Fellowship for her work. Her collections of poetry include Ocean Power: Poems from the Desert (1995) and Jewed'l-hoi/Earth Movements, O'Odham Poems (1996). You can learn more about Zepeda in American Indian, a magazine produced by our National Museum of the American Indian.

Related Posts

Anya Montiel (Tohono O'odham and Mexican descent) is the curator of American and Native American women's art and craft at the Smithsonian, a joint position between the National Museum of the American Indian and the Smithsonian American Art Museum's Renwick Gallery. Her research examines the intersections of Native American art, global arts and crafts, and the art market.

Sara Cohen is the digital audiences and content coordinator for Because of Her Story, the Smithsonian American Women's History Initiative. She shares lesser-known histories of women through this website, the Because of Her Story newsletter, and Smithsonian social media.