Studio portrait of Jovita Idar, ca. 1905. General Photograph Collection/UTSA Libraries Special Collections

By Dr. Tey Marianna Nunn, Director of the American Women’s History Initiative (AWHI), a program of the Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum. Spanish translation by Leila Nilipour, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

“Women recognize their rights, proudly raise their chins and face the struggle. The times of humiliation have passed, women are no longer men’s servants but their equals, their partners.” — Jovita Idar

“Educate a woman and you educate a family.” —Jovita Idar

On August 14, 2023, the United States Mint officially released the latest coin in the American Women Quarters™ Program. Continuing through 2025, the U.S. Mint is releasing new quarters that honor the accomplishments and contributions made by women to the development and history of our country.

Previously issued quarters of 2023 feature composer and educator Edith Kanakaʻole and pilot Bessie Coleman.

This new shiny coin features a striking portrait of journalist Jovita Idar. Her sculpted blouse on the quarter is filled with words describing her impact to not only her home state of Texas, but also to an expansive history of the Borderlands connecting the United States and Mexico. These words include: Mexican American rights, teacher, journalist, nurse, La Cruz Blanca, and the names of all the newspapers she wrote for. It also includes one of her personally significant pen names: Astrea, the Greek Goddess of Justice.

We invite you to explore Jovita Idar’s contributions to American History.

Jovita Idar (1885-1946)

Jovita Idar was born in Laredo, Texas on September 17, 1885. She was one of eight children of Jovita and Nicasio Idar. As a young woman, Idar went to the Holding Institute in Laredo, a Methodist school where she graduated with a teaching certificate.

Her first job was in a segregated Spanish-speaking school in Los Ojuelos, Texas. There she experienced firsthand the state funding inequities between schools for Anglo American students and those for Mexican American students. Idar witnessed extreme poverty and substandard conditions including run-down school houses and lack of school books and supplies for the area’s immigrant youth.

Galvanized by these issues of injustice, Idar realized how systematic racism affected the mostly Tejano and Mexican immigrant communities. She wanted to do more to help so she left her teaching position and joined her father and brothers at the family newspaper, La Crónica, a weekly Spanish language periodical. During this time period there were Jim Crow laws in effect in South Texas and there were deep racial tensions. Lynchings, including those of Mexicans and Mexican Americans, were increasing. Idar made it her mission to cover these crimes for the paper. She also wrote poetry and other articles. Often, she used a different symbolic pen name, “A.V. (Ave) Negra”, or “Black Bird” in English.

As she publicly began to address civil rights, she also championed the rights of women and the importance of women’s independence from men through education. In 1911 she wrote a persuasive article on women’s suffrage for La Crónica. That same year she helped organize a transborder human rights gathering called “El Primer Congreso Mexicanista” (First Mexicanist Congress). Held from September 14–22, 1911. This congreso was one of the first gatherings focused on the economics and social issues impacting the Spanish-speaking peoples of Texas and the US Mexican border.

The participation of women in the Congreso was great and this inspired Idar to found “La Liga Feminil Mexicanista” (The League of Mexican American Women) in October 1911. La Liga was a charitable and political organization that provided Tejano and Mexican immigrant children with educational instruction in an effort to equalize classist and racist policies in Texas schools. It also supported women’s study sessions and promoted financial independence for women on both sides of the border. Idar served as La Liga’s first president and started El Estudiante, a weekly bilingual newspaper geared specifically towards educators.

In 1913 Idar volunteered with La Cruz Blanca, the Mexican version of the Red Cross. This was during the Mexican Revolution which was unfolding across Mexico and along the borderlands. At the time, the Red Cross would not treat insurgents. Through La Cruz Blanca, a neutral entity, Idar worked as a nurse to help all soldiers and others affected by the fighting.

By 1914 Jovita Idar worked at another Spanish language newspaper, El Progreso. She wrote editorials for the paper including one that criticized President Woodrow Wilson’s use of military force along the U.S. border. Her writing angered the Texas Rangers so much that they showed up at the El Progreso office with the intent of shutting the paper down. Jovita Idar blocked the building’s entrance and defended her and the paper’s first amendment rights. Her actions caused the Rangers to leave but they returned later to destroy the offices causing the newspaper to close.

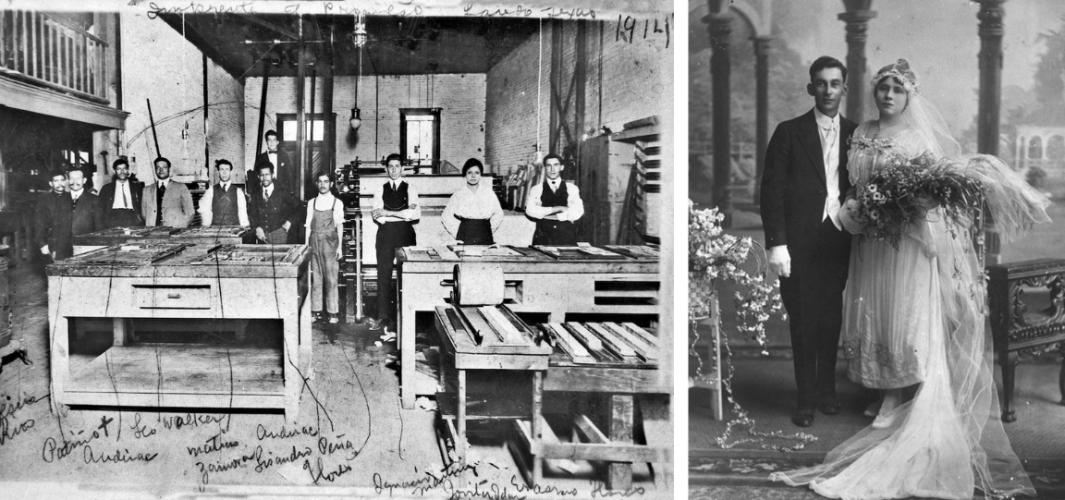

Employees in the print shop of El Progreso newspaper. Jovita Idar is second from the right. General Photograph Collection/UTSA Libraries Special Collections. Right: Wedding portrait of Bartolo Juárez and Jovita Idar. General Photograph Collection/UTSA Libraries Special Collections

After returning to La Crónica to run the family’s newspaper when her father died, Idar started her own newspaper, Evolución in 1916. In 1917 she married Bartolo Juárez and moved to San Antonio where she continued her community activism. She expanded her educational work and started free kindergartens for Spanish-speaking children. Idar also became involved in politics, often convening groups to discuss the latest happenings. She served as a translator for Spanish-speaking patients at the County Hospital and wrote for a Methodist Spanish language newspaper, El Herald Cristiano.

Jovita Idar was a multi-talented force throughout South Texas. Alongside her civil rights and women’s rights activism, she was an early 20th century champion of bilingual education and transborder relations. Jovita Idar died in 1946 in San Antonio. On September 21, 2020, Google honored her with a “Google Doodle.”