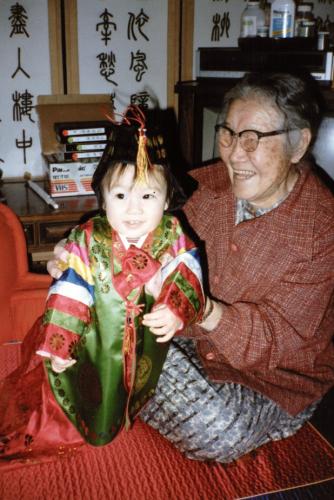

Nicole with her great-grandmother Sung Hark (Lee) Kang in 1986. Photo courtesy of Nicole Kang Ferraiolo.

An interview with Nicole Kang Ferraiolo, Head of Digital Strategies for the Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum, discussing how her great-grandmother’s oral history underlined the importance of grassroots efforts for historical preservation.

Our first digital exhibition, Becoming Visible: Bringing American Women’s History into Focus, is all about highlighting and preserving the stories of five women whose contributions have been overlooked by history. What is your personal connection to the way women’s histories are recorded, obscured, and/or lost?

I have four biological great-grandmothers, and it strikes me that I only know the story of one of them. My great-grandma Kang was one of the first 1000 or so Korean women who came to the U.S. via Hawai’i as a mail-order picture bride between 1910–1924. I’ve been thinking about why this story has endured and the other three haven’t.

I only have about a sentence of information about each of my other great-grandmothers. My great-grandmother Aggie was a second-generation Korean American who had a reputation for being beautiful and a little wild, and she died of tuberculosis in a sanatorium in Honolulu. My great-grandmother Adelaide immigrated from Italy and sold pizza from a pushcart in New York City. I don’t know if I’ve ever even known the name of my fourth great-grandmother, but I know she had 13 children whom she raised in a one-room homestead in South Carolina without floors, electricity, or running water. In all three cases, there is a story there–and one that captures a unique and interesting moment in U.S. history. So why were these stories forgotten, and why did my Grandma Kang’s endure?

I think there are two key differences. The first is that Grandma Kang fundamentally believed in the significance of her own story. She told it to her children, she told it to her grandchildren, and she participated in oral history projects. The second difference is that she was connected to a grassroots community that made preserving its own history a priority.

In most cases, it takes about two to five generations for a person to be forgotten. If stories aren’t recorded and preserved, it’s only a matter of time before we lose them.

Tell me about your Grandma Kang’s story.

Sung Hark (Lee) Kang was born in 1900 in Pusan, Korea. She was the daughter of a wealthy silk merchant and had loving but old-fashioned parents. Like her mother before her, she loved learning and dreamed of an education. At age 17, she ran away from home to go to school in Tokyo where some of her friends were studying. When she arrived, she quickly ran out of money and could not attend the school. She wrote to her parents about returning to Korea, but they told her they had faked her death to protect the family name and she could never come home.

While working in a western-style shoe shop in Yokohama, she encountered Korean picture brides buying shoes before their journey to Hawai’i. She met a man there who suggested she consider going herself because American money was worth twice as much as Japanese money. Due to immigration laws, the only way for her to emigrate was as a bride. The man assured her that he could find her a match, and she could decide if she actually wanted to go through with the marriage after meeting her partner.

She decided to make the move. In her mind, it was an engagement in name only, and, once she arrived in Hawai’i, she’d be able to find work and go to school. However, when she got there, she was denied entrance twice for medical reasons. She was required to return to Korea and then travel back to Hawai’i, where she was detained in an immigration center for months until she got medical clearance. Due to the high cost my great-grandfather incurred for this delay, she felt obliged to go through with the marriage. The marriage was not a happy one. They lived and worked under brutal conditions on sugar plantations, first on Kauai, and later in Honolulu, where they worked 10-hour days, six days per week for only $22 per month (70 cents per day).

Sung Hark (Lee) Kang and her children in Hawai’i around 1930. Photo courtesy of Nicole Kang Ferraiolo.

She formed strong bonds with her Japanese and Native Hawaiian neighbors, and they helped watch her five kids so she could study to become a seamstress and get her family off the plantation. She became a dress maker for naval officers’ wives and was finally able to divorce her husband. She lived comfortably in Honolulu until Pearl Harbor, after which she faced harassment and threats of violence for being East Asian. She then moved with several of her children to San Francisco.

When her youngest son got a football scholarship at a college in Oregon, she visited him and found a vibrant community of Korean-American farmers living in the town of Gresham, outside of Portland. While there, she saw people she knew there from both Hawai’i and Korea. She convinced her son Moon Chu Kang (my Grandpa Mooney) to buy a 20-acre farm with her where they would all live, growing strawberries in the summer and cabbage in the winter.

Unfortunately, no one in the family had any idea how to run a farm, and they struggled financially for years. It was tough, particularly for the younger generation, but Grandma Kang was possibly the happiest she had ever been. She became the matriarch of a big dynamic family and was surrounded by her children and grandchildren. She had a boyfriend who was a doctor. And she never stopped reading and learning! By the end of her life at age 96, she was a respected elder and leader in her local Korean American community.

Black and white portrait of Dr. Chung and Sung Hark (Lee) Kang sitting side by side, unsmiling, facing the camera.

What has it meant to you to find your great-grandmother’s oral history?

Prior to reading the transcripts of her oral histories, I knew only the basic outline of her story. I came across a published collection of oral histories by Sonia Shinn Sunoo, who interviewed 28 Korean picture brides in the 1970s, including my Grandma Kang. I also found a second oral history transcript by the Korean American Historical Society, which was accompanied by interviews with four other members of our family. In total, it comes to over 50 pages of first-person accounts about her life!

There was so much there that wasn’t in the stories shared with me as a kid. For instance, I had no idea how involved she was with the Korean independence movement. She was the secretary of the Korean Women’s Relief Society of Hawai’i, where she led fundraising campaigns for the independence movement and even hosted leaders of the Korean Provisional Government in exile in Shanghai. She had this whole history of activism and anti-colonial organizing that I had no idea about!

Sung Hark (Lee) Kang around 1990. Photo courtesy of Nicole Kang Ferraiolo.

From this experience, what have you learned about the importance of grassroots and community efforts in preserving history?

It’s not lost on me that I wouldn’t know this history if it were not for one oral historian and a local historical association who believed these stories were worth saving. Grandma Kang’s oral history, along with the 27 others featured in Sunoo’s collection, are now some of the best records we have about this first wave of Korean American women. They’ve been cited in dozens if not hundreds of academic books and articles, and they’ve helped inspire award-winning fiction books and national bestsellers.

As we build the Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum, we’re doing it with the understanding that this museum will outlive us all. Our understanding of historical significance changes over time, and the stories we might have ignored can become the ones we yearn for decades later. This is one of the reasons our museum has placed such a high priority on community co-creation. We recognize that grassroots community organizations have been doing critical memory work for a long time. We hope to use our platform as a national museum to support these efforts and amplify these stories.

Join us in the collaborative project of preserving women’s history. Check this webpage for updates and opportunities to co-create with us.