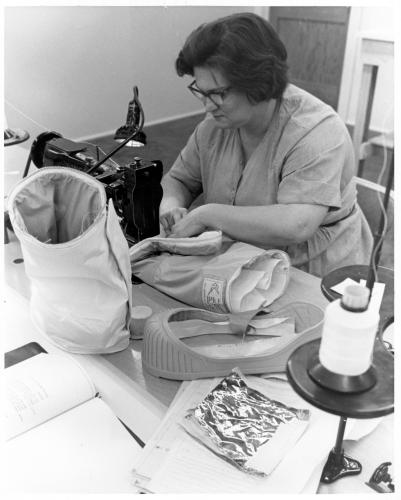

Hazel Fellows, seated, machine-sewing pieces of an Apollo A7L spacesuit on the production line at International Latex Corporation (ILC), Federica (Dover), Delaware; photograph released August 9, 1968. Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

Appearing in a widely circulated photograph from 1968, Hazel Fellows has come to represent the group of women pattern cutters, seamstresses, and assemblers working at the International Latex Corporation (ILC) who made the spacesuits for the Apollo program from 1962-1974. Though not much is known about these women individually, collectively, they were working-class women who had learned to sew from their mothers or in high school home economics classes. Some of the women had worked for Playtex, the consumer division of ILC that produced girdles, bras, and rubber pants to go over baby diapers. Others came from nearby clothing and luggage manufacturers. All were highly skilled in clothing and textile trades. They became personally invested in the national effort to send a person to the moon and recognized that astronauts' lives depended on the durability and performance of the spacesuits.

Torso detail of the spacesuit cut, sewn, and assembled by the women working at the International Latex Corporation. Worn by Neil Armstrong in 1969. Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, Transferred from NASA.

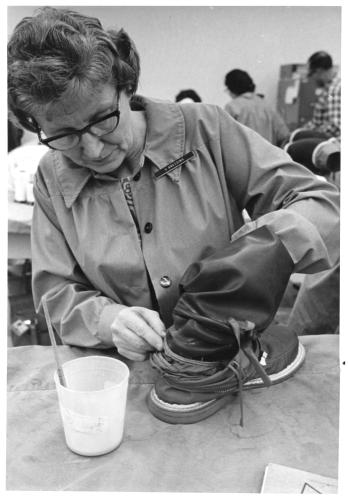

Fellows was not the only African American working at ILC. In fact, the company was known for hiring skilled African American workers. Iona Allen was another African American seamstress remembered for her ability to complete the most difficult sewing tasks—for example, she constructed Neil Armstrong’s lunar boots. Every component of the spacesuit required precision work while adapting to new processes and materials.

Detail of boots and legs of the Apollo spacesuit sewn by Iona Allen and worn by Neil Armstrong in 1969. Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, Transferred from NASA.

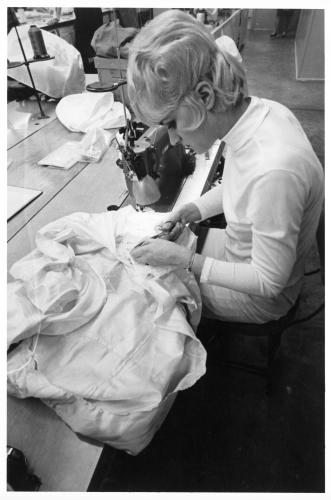

The seamstresses blended their practical knowledge with the engineering process to innovate designs and procedures. Suit engineers relied upon the women’s experience of handling textiles and clothing. In the development phase of the suits, the seamstresses figured out which hand and machine sewn techniques would accomplish the engineers' designs and helped establish the procedures used to put the different components together. The women then followed detailed written instructions as they cut, sewed, and assembled with adhesive or other bonding material.

One way that the seamstresses’ practical experience influenced the process was in the use of sewing equipment. For example, Francine Burris refused to let her team use electric scissors when cutting out the pieces for the delicate mylar layer in the thermal micrometeoroid garment. Accuracy depended upon the control of the scissors and speed would not help the process. The sewing machines also moved at a fraction of their normal rate. The spacesuits required a higher standard of production than those typical of clothing manufacture. There was practically no tolerance for error or variation. Mistakes caused delays and wasted costly materials. Not much talk occurred on the work floor as the women concentrated on their tasks.

Unidentified woman on the Apollo A7L spacesuit production line at International Latex Corporation (ILC), Frederica (Dover), Delaware, sits at a special long-armed sewing machine assembling spacesuit components. Woman is seen through the opening of the machine. Photograph released May 14, 1968. Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

Unidentified woman seated at a sewing machine, assembling components of lunar overshoes designed to be worn over an Apollo A7L spacesuit for extra-vehicular activity (EVA) on the surface of the moon; part of the production line at International Latex Corporation (ILC), Frederica (Dover), Delaware. Photograph released May 14, 1968. Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

Forgetting to remove a pin was a common sewing mistake that could be life threatening in a spacesuit. The supervisor at ILC’s Frederica plant, Eleanor Foraker, realized this early on and assigned different colored pins to each seamstress. Since the women had to account for all the pins they used at the end of a shift, there was never any question about who left a pin behind. Foraker was known to surprise the responsible seamstress with a pin stick as a reminder of the hazard.

To meet production deadlines, the women put in long hours, often working on weekends. Nevertheless, a 1971 video produced by NASA shows astronaut Charlie Duke being fitted for his spacesuit and yet fails to recognize the efforts of the women making the suits. While their work is shown in the video, their names and voices are not, demonstrating the ease with which their contributions were erased.1

Henrietta Crawford, seated at sewing machine, assembling suit pieces on the Apollo A7L spacesuit production line at International Latex Corporation (ILC), Federica (Dover), Delaware. Photograph released May 14, 1968. Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

Velma Breeding assembling boot components on the Apollo A7L spacesuit production line at International Latex Corporation (ILC), Frederica (Dover), Delaware. Photograph released May 14, 1968. Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

Though their names have largely been left out of historical records, there was at least one occasion when a seamstress’ skills saved the launch. Three days before the launch of Apollo 17 in December 1972, one of the spacesuits needed major repair, and using the backup suit was not an option. ILC sent Roberta Pilkenton to Florida with the briefcase holding the replacement part handcuffed to her wrist. She had never flown before, and the idea terrified her. However, she had the most experience working with the neoprene leg joint needing repair, so Pilkenton went. She began working soon after her arrival at the Kennedy Space Center at 4:00 am and had the repair completed by midnight.

In a 1994 interview, Pilkenton stated “We were all good and we were a team. You don’t get anything done unless you are a team.”2 Reaching the moon harnessed the imagination and commitment of the entire nation. When President Kennedy presented his plan to Congress in May 1961 he stated “It will not be one man going to the Moon. . .it will be an entire nation. For all of us must work to put him there.”3 The women making the spacesuits were part of an estimated 400,000 people directly involved in placing 12 astronauts on the moon during the Apollo program. It was their mission to ensure the integrity of the spacesuits and the safety of the men who wore them.

Endnotes:

1 NASA, Moon Spacewear, 1971, National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, NAID 4148157.

2 Oral history interview with Douglas N. Lantry on October 25, 1994. Hagley Digital Archives ID: AUD_2021204_B01_ID02. https://digital.hagley.org.

3 NASA,“The Decision to Go to the Moon: President John F. Kennedy’s May 25, 1961 Speech before a Joint Session of Congress,” May 25, 1961, https://www.nasa.gov/history/the-decision-to-go-to-the-moon/.

Further Reading:

- Bill Ayrey, Lunar Outfitters: Making the Apollo Space Suit, 2020

- Nicholas De Monchaux, Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo, 2011.

- Douglas N. Lantry, “Man in Machine: Apollo-Era Space Suits as Artifacts of Technology and Culture,” Winterthur Portfolio 30 no. 4 (Winter 1995): 203-230.

Related Posts

Diana Turnbow provides research and project support to the Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum.