Civil War era surgeon, women’s rights and dress reform advocate

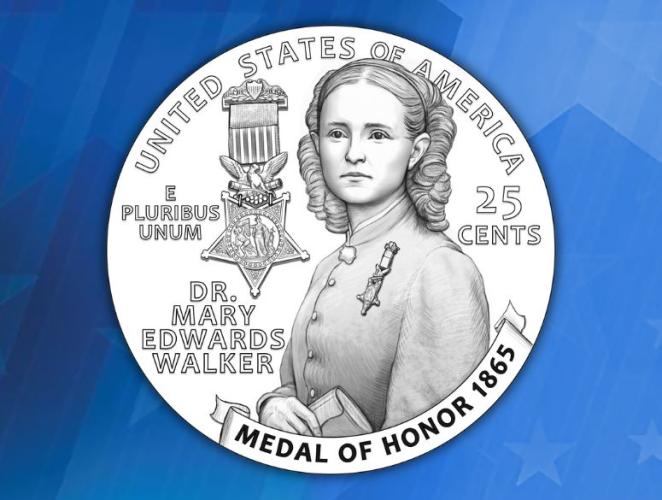

American Women's Quarter Program

Early Life

Born outside of Oswego, New York, Mary Edwards Walker was one of seven children to Alvah and Vesta Walker. A progressive couple, the Walkers raised their children with gender and racial equality in mind: the family split domestic work equally among everyone, the Walker parents opened the first free school in Oswego with all five of their daughters attending, the family farm sheltered freedom seekers on the Underground Railroad, and all the girls were encouraged to pursue higher education and professional careers.

In 1855, Walker graduated from Syracuse Medical College, making her only the second female doctor in American history (the first, Elizabeth Blackwell, graduated from Geneva Medical College in Geneva, New York, only six years prior). Shortly after completing her studies, Walker and a fellow medical student, Albert Miller, married and started a private practice in Rome, New York. Continuing her habit of living her progressive values and viewpoints, Walker refused to agree to “obey” Miller in their wedding vows, kept her maiden name, and wore a short skirt with trousers—which she called Reform Dress—during the wedding ceremony. By 1859, both the couple’s medical practice and marriage had failed; after a ten-year separation, Walker filed for divorce on the grounds of Miller’s infidelity. It was an act that stigmatized her for the remainder of her life as anti-marriage or anti-family, two unfathomable concepts for women in American society at the time.

Civil War Era

At the start of the American Civil War, Walker felt compelled to aid the Union cause. Initially, she traveled to Washington, D.C. with the intention of joining the Army as a surgeon, thinking their need for trained medical professionals would outweigh their reluctance to accept a female doctor. She was mistaken, and her request for an official commission was denied. Undeterred, Walker began volunteering as an assistant surgeon at a makeshift hospital in the U.S. Patent Office (now home to the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery and Smithsonian American Art Museum).

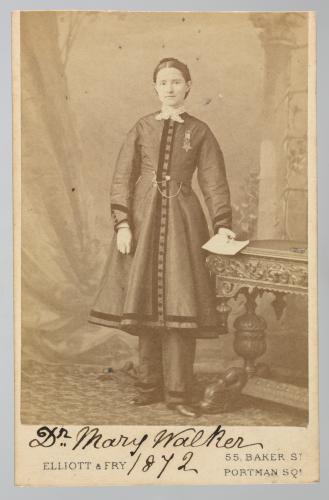

To allow for as much movement and comfort as possible while working on the injured, she abandoned the traditional long skirts and corsets, preferring instead to wear a skirt/trouser combo which she paired with a feminine hairstyle so people would be able to identify her as female. During this time, Walker helped establish the Women’s Relief Organization which sought to aid the female family members that came to visit wounded loved ones in the military hospital. Throughout her time in D.C., Walker faced open hostility and abuse for her nonconformance to gender norms, but her medical expertise and the respect she earned for the treatment she gave to soldiers and civilians alike, eventually overcame.

1872 photograph of Dr. Mary Edwards Walker wearing the dress and trouser combination from her time as a surgeon for the Union Army. Image courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

By the end of 1862, Walker was taken in as a Union field surgeon—though still as a non-commissioned volunteer—where she worked near the frontlines during the battles in Fredericksburg, Virginia, and Chattanooga, Tennessee. During this time, Walker never stopped petitioning for a commission as an Army surgeon, going so far as to appeal directly to both Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton, and President Abraham Lincoln. In response, she was promoted to “Contract Acting Assistant Surgeon (civilian)” for the 52nd Ohio Regiment, the closest she would ever come to a formal enlistment.1

On April 10, 1864, Walker’s life forever changed. While in Confederate-controlled territory, she was captured and sent to military prison at Castle Thunder in Richmond, Virginia. Like many prisons during the war, Castle Thunder became increasingly overcrowded with an estimated 700 to 1000 prisoners held at the time of Walker’s arrival. Additionally, the reputation of Castle Thunder guards was one of such extreme cruelty that the Confederate House of Representatives conducted an investigation for “excessive brutality and accidental shootings of prisoners.”2 Although Walker was only at Castle Thunder for a few months, during that time she experienced severe weight loss, suffered from bronchitis, and experienced a permanent loss in eyesight that is partially responsible for her leaving the medical field shortly after the end of the Civil War.3 Walker was released in exchange for a Confederate surgeon in August 1864. Throughout the remainder of her life, she openly referred to this prisoner exchange as validation from the Army4 and said that she was delighted in being part of a “man for man” swap.5

Congressional Medal of Honor

No stranger to situations that required her to bravely face gender discrimination head-on, Walker fought for a military pension after the Civil War. Yet again, the Army’s unwillingness to allow her a formal enlistment waylaid her plans. Instead, President Andrew Jackson awarded her a Congressional Medal of Honor in 1865, making her the first woman to receive the prestigious award. Nearly 160 years later, she remains the sole female recipient.

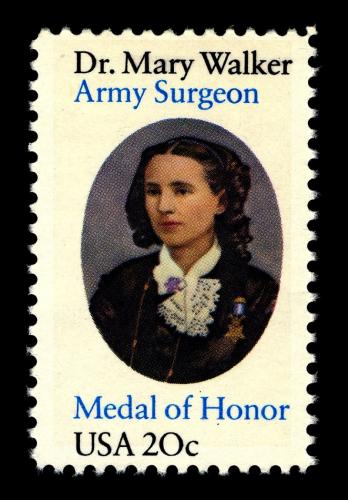

The official award reads, in part, that Dr. Mary E. Walker “has rendered valuable service to the Government, and her efforts have been earnest and untiring in a variety of ways.”6 These words notably omit any mention to active combat service, which, according to the revised standards for the award (issued in 1916), disqualified Walker and 910 other recipients from their medals. Walker refused to return her medal, proudly wearing it on her chest every day for the remaining two years of her life. Sixty years later, after years of work by her descendants, Dr. Mary Edwards Walker’s Congressional Medal of Honor was restored in 1977.

U.S. postage stamp from 1982, depicting Dr. Mary Edwards Walker with her Medal of Honor. Image courtesy of the National Postal Museum. Copyright United States Postal Service. All rights reserved.

Social Activism

Rather unsurprisingly, Walker was an outspoken advocate for women’s rights and equality. Following the end to her medical career, she dedicated her time to advancing her social activism and became entrenched in the suffragist movement, worked to secure military pensions for wartime nurses, and became a proponent of dress reform. Over time, the work Walker did for voting rights brought her into the social networks of Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, where they fought alongside one another despite divergent opinions. Unlike the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), which advocated for a Constitutional Amendment guaranteeing a woman’s right to vote, Walker proposed that no amendment was needed as the Constitution already granted them the right—it just needed to be enforced. To prove her point, Walker attempted to vote in the 1871 election but was denied. Unfortunately, despite their shared goal, the different paths that Walker and NWSA wanted to take to get there eventually resulted in them parting ways.

Walker’s preference for clothes that were socially acceptable for men to wear didn’t stop at trousers; as she got older, she began incorporating suit jackets and top hats into her wardrobe. Never one to shy away from controversy, these clothing choices put a spotlight on her that she refused to hide from. In 1870, she was arrested in New Orleans for impersonating a man, and in both 1912 and 1914 she testified to the U.S. House of Representatives about women’s suffrage while wearing a pantsuit. She even opted to be buried in a black jacket and matching trousers. Walker is quoted as saying, “I don’t wear men’s clothes. I wear my clothes.”7

Learn More

The National Postal Museum has created an online collection of Smithsonian objects related to Dr. Mary Edwards Walker.

Notes:

Further Reading:

Related Posts

By Jessie Aucoin, Director of the Department of Education & Visitor Experience, National Postal Museum