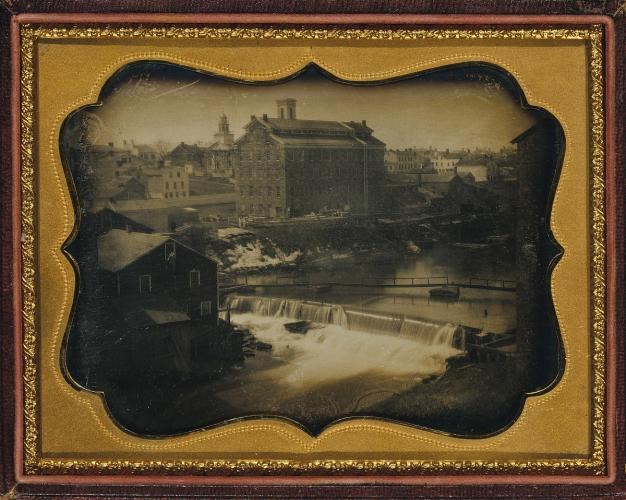

Unidentified, [Seneca Falls, New York (upstream)], ca. 1850, daguerreotype, plate: 4 1⁄4 x 5 1⁄2 in. (10.8 x 14.0 cm.), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase from the Charles Isaacs Collection made possible in part by the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment, 1994.91.232

By Jennifer Schneider

This July marks the 175th anniversary of the Seneca Falls Convention, which took place on July 19 and 20, 1848. This significant moment allows us to think critically about the historic narrative that has been handed down over the last century. It’s not a coincidence that the convention was held in upstate New York, which had long been a center of abolitionist – or anti-slavery – activity. The women’s rights movement, and the push for voting rights for women, grew out of the anti-slavery movement of the early 1800s.

Seneca Falls was the first women’s rights convention and was organized by a group of five women: Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Coffin Mott, Martha Coffin Wright, Mary Ann McClintock, and Jane Hunt. They discussed their lives and challenges over tea, then decided that they should do something. They placed an advertisement in local newspapers about “a Convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition of woman.”

Stanton, working with Elizabeth McClintock, would spend the next eight days drafting the Declaration of Sentiments on a table in McClintock’s parlor. That table is now in the Smithsonian’s collections.

The Declaration of Sentiments was modeled after the Declaration of Independence. It chastised men for how nineteenth century society treated women. It included a list of sixteen demands to improve the lives of women, including the right to an education, the right to own property, and the right to vote in public elections.

About 300 people, including both women and men, attended the convention on women’s rights. The discussion of the proposed list of eleven sentiments was lively. The radical demand for woman suffrage, or women’s right to vote, caused the greatest amount of discussion. It nearly did not pass the convention, but in the end, the attendees were persuaded.

While many think Susan B. Anthony attended the Seneca Falls Convention, she did not. Stanton and Anthony would not meet for the first time until 1851, three years after the convention. The two would become lifelong allies in the fight for woman suffrage.

Frederick Douglass, a former slave, an abolitionist, and a talented public speaker, attended as a supporter of women’s rights. He spoke at the convention on behalf of women’s right to vote. He would become one of 100 signers of the Declaration of Sentiments, and one of thirty-two men to sign the document. Douglass would go on to publish in The North Star, the newspaper he edited, in support of women’s rights.

Stanton and Anthony, along with Douglass, would help found the American Equal Rights Association (AERA) in 1866. The AERA worked for all American citizens, regardless of race or gender, to gain the right to vote in public elections. However, when the AERA agreed to support the 15th Amendment, which passed in 1869, Stanton and Anthony split with the AERA because they felt woman suffrage should have been prioritized over Black male suffrage.1 The two women then founded the National Woman Suffrage Association in May 1869, which advocated for the right to vote for white women only. Their legacy would be tarnished by this division and further racist remarks made as they sought for white women to be granted the ballot at the expense of Black men.

The American Woman Suffrage Association was founded in November 1869 in response to the NWSA. The AWSA, with Lucy Stone as president, would advocate for the right to vote for all Americans regardless of their race, color, or gender. They took two different strategies towards woman suffrage, with the NWSA working for a federal amendment to the constitution, and the AWSA working at the state level for women to be granted the vote. The two organizations would remain rivals until they merged in 1890 to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).

Stanton and Anthony would be the primary editors of A History of Woman Suffrage, a three-volume history of the women’s voting rights movement written from 1876-1886. These books cemented their legacy–and the myth of the Seneca Falls Convention as the start of the American women’s rights movement–into the historical narrative of the United States.2 By writing their own history, they would prioritize the NWSA’s accomplishments and downplay the AWSA’s contributions to the suffrage movement.3

In 1919, the 19th Amendment to the constitution was passed by Congress and sent to the states for ratification. Then the NAWSA reached out to the Smithsonian about donating the “Declaration of Sentiments” table above, further anchoring the Seneca Falls Convention as a pivotal moment in the history of women’s rights in the U.S.

Seventy-two years after the Seneca Falls Convention, the 19th amendment was ratified by thirty-six states. It meant that United States, and individual states, could not deny the right to vote on the basis of sex. This effectively granted white women the right to vote in local and national levels, but it did little to help women of color. Many states would bar Native Americans from voting until 1957. Latina, Black, and Asian American women would still face opposition at the polls through literacy tests and poll taxes until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which prohibits racial discrimination in voting.

Then the suffragists turned their attention to rally women to vote in elections. The League of Women Voters was founded by NAWSA president Carrie Chapman Catt in 1920 after the ratification of the 19th amendment. Today, the nonprofit continues to encourage women to exercise their right to vote and participate in the political process.

1 Stanton and Anthony were a product of their times, and this is reflected in the racist rhetoric they repeatedly used as they sought for white women to be granted the ballot at the expense of Black men.

2 Tetrault, Lisa. 2014. The Myth of Seneca Falls: Memory and the Women’s Suffrage Movement, 1848-1898. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press.

3 Ridarsky, Christine L., Mary Margaret Huth, and Nancy A. Hewitt. 2012. Susan B. Anthony and the Struggle for Equal Rights. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.