Pinback button featuring a portrait of Bessie Coleman, mid to late 20th century. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift from Dawn Simon Spears and Alvin Spears, Sr.

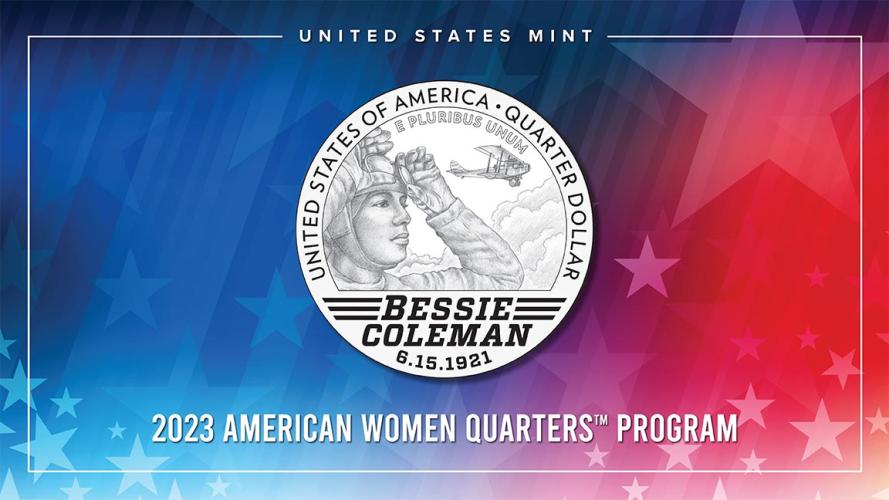

Today the U.S. Mint released a quarter featuring pilot Bessie Coleman as a part of the American Women Quarters™ Program. This program celebrates the accomplishments and contributions made by women to the development and history of our country. Coleman’s quarter is marked with the date June 15, 2021, to mark the recent 100th anniversary of the date she became the first African American woman to earn a pilot's license.

Image of 2023 Bessie Coleman quarter, part of the American Women Quarters™ Program. Copyright United States Mint. Used with permission.

Through the rest of this year, the Mint will issue four more quarters featuring notable women on the reverse (tails side):

- Hawaiian composer and custodian of native culture and traditions Edith Kanakaʻole

- First Lady and humanitarian Eleanor Roosevelt

- Journalist and activist Jovita Idár

- Prima ballerina Maria Tallchief (Osage)

We will share more about each woman as their quarters are released.

Staff at the Smithsonian American Women's History Initiative, Because of Her Story, are excited to help bring this series to life with the U.S. Mint and the National Women's History Museum.

We invite you to explore Bessie Coleman’s contributions to American History.

Pilot Bessie Coleman

On June 15, 1921, Bessie Coleman became the first African American woman and first woman with Native American ancestry to earn a pilot’s license.

Coleman was born in 1892 in Atlanta, Texas. She was one of 13 children. Her mother worked as a domestic servant for a white family and her father was a day laborer. Her father, who had three Native American grandparents (likely from the Choctaw or Cherokee Nations) later moved to Oklahoma without the rest of the family. Her eldest siblings moved to Chicago, Illinois, searching for better job opportunities. Coleman joined her siblings in 1915 and trained to become a beautician. In 1916 she won a contest that declared her the best manicurist in Black Chicago.

Coleman’s brother John, a World War I veteran, told his sister about French women pilots. He taunted his sister about the lack of opportunities for Black women in the United States. He said they would never be allowed to fly planes. Instead of being discouraged, Coleman took this as a challenge and replied, “That’s it! You just called it for me.”

For Coleman, this revelation spurred the arduous process of earning a pilot’s license. She applied to flight schools in the United States, but they denied her entry because of their biases about her race and gender. With countless refusals in hand, she confided in Robert S. Abbott., the powerful founder, editor, and publisher of The Chicago Defender, the most widely circulated Black newspaper in the country. Abbot recognized Coleman’s commitment and a great news story if she was successful. Abbott advised her to apply to a flight school in France.

Bessie Coleman passport picture. National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution. (SI-92-16052-A)

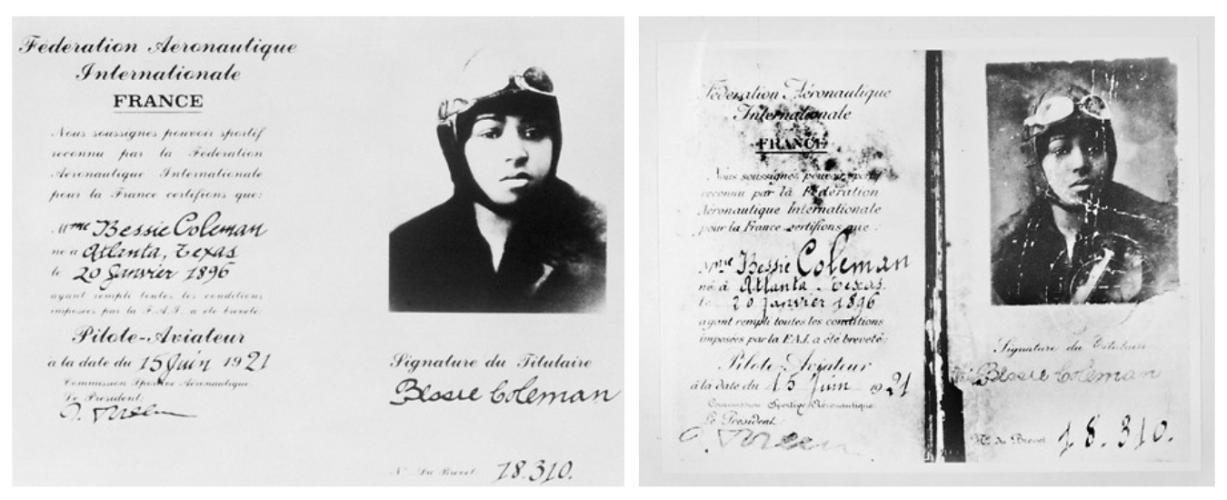

Coleman quickly learned French, gathered her savings, and crossed the Atlantic Ocean to learn to fly at the Caudron Brothers School of Aviation. “I knew the Race needed to be represented,” she told The Chicago Defender, “so, I thought it my duty to risk my life to learn aviating.” Coleman earned her pilot’s license on June 15, 1921, from The Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. Ten months after her move to Paris, she returned to the United States, but quickly realized that she needed more training before she could safely perform stunts for crowds. She returned to France and Germany to train with veteran World War I pilots.

Bessie Coleman Fédération Aéronautique Internationale aviation license. National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution. (Left: SI 99-15416-S, Right: SI 93-7758-S)

On September 3, 1922, in Long Island, New York, Coleman made the first public flight by an African American woman in the United States. Although she had success in her first few shows, she struggled to become a regular performer. Intrigued by an advertising opportunity with Coast Tire and Rubber of Oakland, Coleman moved to California. She hoped to break into Barnstorming, a popular sensation of the 1920s that attracted large audiences. Barnstormers would fly figure eights, flip upside-down, walk onto the wings of their plane mid-flight and sell rides to the public.

In 1925, Coleman began a multi-city tour throughout the South. Her first performance was in Houston, Texas. She refused to participate in any shows where organizers racially segregated crowds. African American audiences, especially women, enjoyed her shows and offered support in the form of food and lodging. Sometimes, instead of performing, she would give speeches about her life experiences. She often made more money from lectures than flying.

Bessie Coleman with a Curtiss JN-4D Jenny. National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution. (SI-92-13721)

A year later, she was in Jacksonville, Florida, preparing for a performance. Coleman sat in the passenger’s seat of her newly purchased Curtiss Jenny biplane. Her seatbelt was unbuckled, allowing her to survey the area for a suitable parachute landing site. Her mechanic and publicity agent, William Wills, flew the plane when it suddenly flipped over and nose-dived. Coleman was tragically thrown from the uncovered roof to her death. Wills also died in the accident. Later, authorities discovered that a wrench accidentally lodged in the control gears caused the devastating accident.

Coleman shared her knowledge and love of flight with many African Americans, especially fellow women. She dreamed of opening a flying school in the United States for African American men and women. She had saved earnings from her performances and lectures to fund her mission. Her tragic death occurred before she could achieve her goal.

Many others stepped in to carry on her legacy. Memorial ceremonies and her funeral in Chicago were attended by thousands. The eulogy was delivered by activist and journalist Ida B. Wells. In 1934, African American pilot William Powell dedicated his thinly veiled autobiography, Black Wings, to Coleman, writing that she “displayed courage equal to that of the most daring men.” He also carried out Coleman’s dream of opening a flight school for African Americans and named it in her honor.

Read more about Bessie Coleman, her legacy, and other early aviators from the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.